This substack, and my life, apparently, is about creating a future we want—a future for the well-being of all. I believe realizing that vision requires an evaluative evolution. For twenty-five years, mostly in hiding, I've been working through philosophical and practical frameworks for what that means and how we can bring that future into our lives.

An evaluative evolution presents us with a choice: we can accept what the world we have built gives us, or, with intention and purpose, vision and create a future we want.

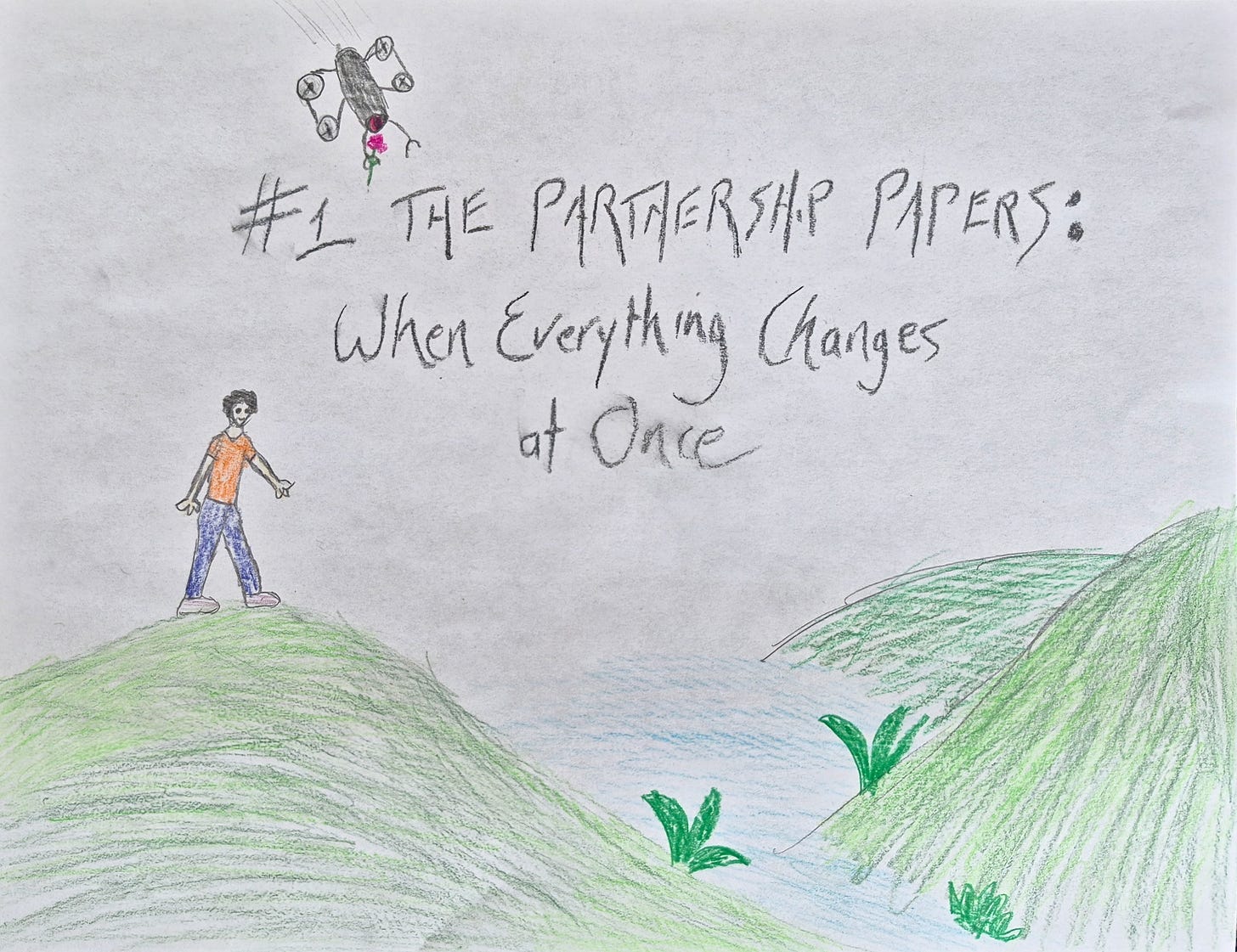

In the coming months, I'm going to share five long papers, section by section, and a few explanatory essays. These are The Partnership Papers. It is not going to be for most people. They are for everyone and everything. For what is most precious about our humanness.

In this first essay I'll share something of my personal path in hopes that it provides meaningful context for what follows. The second essay will provide an overview of each of the papers that follows. The third essay begins The Partnership Papers and is titled: "The Evolutionary Origins of Values Theory: From Cosmic Patterns to Nature-Human-AI Partnership."

A Personal Journey Through Civilization's Breaking Point

I've been confused by nearly everything, always. My daughters say I always have a certain look on my face. I starting learning this look at two years old, watching my father float down from the sky in an orange parachute. What was he doing up there? What were we doing down here? And why didn't we want to go over there? Questions everywhere. Mostly questions I was too afraid to ask.

Kids fought. Nations warred. People starved. Smart = Good = Success. Bad = Stupid = Failure. Compete until you win or die. Lose and fail and quit and be ashamed and feign strength. If I had the courage to ask about any of it, I was reminded that I might as well not ask. None of it made sense, and while that confusion began as passive wondering—it became an active force that would direct my energy allocation for decades.

The first place I found anything resembling responses to these questions was on Delaware's stretch of the Nanticoke River. A ten-year-old beginning a journey that would take thousands of hours and eventually land an older me and that thirteen-foot aluminum V-hull rigged for largemouth bass fishing at the end of the dock, right where it had started.

The river taught me pattern recognition long before I had words for it. I learned how energy flows through relationship networks—how water, land, stillness and motion, osprey, eel, oak, striped bass and ocean, freshwater clam, grass, boat, sand, dragonfly, wind, weather and sky all connected in ways that were both obvious and mysterious but easily recognizable as "river".

What I didn't know then was that I was learning to perceive what I would later call values: the patterns humans notice, bound, and label. The river was one of my first teachers in understanding what I now call the Nhà—the accelerating co-evolution of Nature, Humanity, and AI that defines our current evolutionary moment.

The Conservation Revelation

After college, I spent nearly a year on Costa Rica's Osa Peninsula and visited 40+ countries in my twenties. I'd volunteer at nature conservation projects along the way but I wasn't much help. I was mostly observing. Everywhere, I met passionate people dedicating their lives to protecting something precious—a species, forest, culture, art, language, a people, a Way. Yet I never came away convinced their efforts would survive beyond any meaningful timeframe.

Reefs poisoned, forests burned, pristine reserves loved to death by tourism, communities displaced, heritage broken. Scientists carefully measured extinctions. The rich gave generously to ignorant, often destructive, endeavors. The gaps widening between enormous personal investment, the suffering and destruction, and any semblance of significant and lasting impact were devastating. Massive amounts of energy. Wisdom nowhere to be seen.

The Evaluation Quest and the Missing Information

I took on the challenge of investigating and understanding values in a purposeful, formal way. First I learned that no one really had a good answer as to what they were. At least not one that was helpful to me.

To learn more I worked and studied in the scientific discipline and professional community called "Evaluation" for 20 years. Yes, I was an evaluatoor. Not kidding. It's a real thing. I contributed original research to the discipline, designed evaluations of government programs, and managed professional networks of evaluators (fancy talk for good times with friends at meetings and conferences).

For twelve years at the United States Environmental Protection Agency, I designed systematic approaches to assess whether programs achieved their stated goals. I don't know how many of my colleagues thought about it in the same way, but for me, those goals were always about someone's or something’s values. Those values were the cause of all of the work everyone was doing.

So, looking through my lens, we were evaluating whether these programs were honoring values. But what were they? Where did all of these goals come from? We were assessing values without understanding what they were. Every program existed because, at least initially, humans valued something—clean water, healthy communities, protected environment—but we had no systematic way to understand, measure, assess, or communicate about these values that drove everything. Again, allocating massive amounts of money and time and expertise to something that could hardly be described, much less measured or understood.

Personal Investigations: Learning Through Living

I did not feel like I was learning much about values until I began applying my training and experiences as an evaluator to exploring a series of deeply personal, insanely complex, and relatively universal values. They became the subject of a series of artworks and creative endeavors that grappled with questions that I chose to bring deep inside of me.

"What is a Garden?" became a series of 30 essays about twenty years and a world of vegetables. "What is a River?" flowed into The River Cube Project, an art-science adventure that paddled 300 miles to the Atlantic Ocean with a giant metal cube. "What is a Home?" transformed where our family lived into a sculpture called "Bound Home". "What is Surf?" transcribed my relationship with existence into a collection of 80 meditations called "Surf: A Praxis for Living and Dying."

Each investigation revealed the same pattern: seemingly simple values familiar to most anyone are vast collections of interconnected patterns that resist definition yet remain recognizable. A garden isn't just plants and soil—it's thousands, perhaps trillions, of relationships between sun, water, microbes, human attention, seasonal cycles, aesthetic choices, history, culture, and community connections. This complexity characterizes all values, from justice and beauty to trust and love. These investigations taught me that values are patterns humans perceive, bound, and label in relationship networks—and understanding this is kind of a big deal.

In 2018, severe health issues forced me to leave my work at the Environmental Protection Agency. Equipped with vision, curiosity, and fear, I began full-time homeschooling my daughters, then nine and thirteen. This wasn't just a career change—it became the laboratory for testing ideas that had been developing over decades in confusion. We didn't start with a curriculum. We started with a question: "What does an education look like that will enable us to create a future we want, one for our well-being and the well-being of all?"

This question influences everything we do, and it's become clear that our entire species must grapple with this same question as we navigate unprecedented technological capabilities while dealing with accelerating civilizational challenges.

The Fourth Turning Meets the Polycrisis

We're living through what some historians call a Fourth Turning—one of those rare periods of fundamental societal transformation that occurs roughly every eighty to one hundred years, when the basic assumptions organizing human civilization come apart and reassemble in entirely new configurations. But this time feels different. This time, we're not just experiencing the familiar cycles of social upheaval.

We're witnessing what researchers call a polycrisis: climate change accelerating beyond prediction models, mass extinction eliminating species faster than we can catalog them, economic systems designed for a different age straining under inequity that threatens democratic institutions, pandemic disruptions revealing the fragility of global supply chains, nuclear weapons in the hands of increasingly unstable actors, and shifting world orders as traditional power structures give way to something not yet clear.

The Ultimate Manifestation of Hubris

On top of everything else, we're creating the most powerful technology in human history—artificial intelligence systems that could surpass human capabilities within years rather than generations. Unlike previous technological revolutions—agriculture, industrialization, even the internet—that unfolded over decades and centuries, that allowed societies to use a strategy of trial-and-error, AI development occurs at evolutionarily alien timescales. The acceleration is so rapid and the power that is up for grabs is so great that there are likely many fewer trials we can run before the errors deliver irrevocable, perhaps undetected and inconceivable, harms.

Nations and corporations and people who have enormous power concentrated around them are racing, essentially spinning up an arms race to create AGI—an unprecedented, unknown, most powerful invention that humanity has ever conceived. This creates a new existential risk, if not to our species then to much of what we recognize as humanness and nature and much of what we today would call familiar. We are racing and so we may get to AGI very fast. But will we look up and find ourselves in the place that we want to be?

I don't sleep too well anyway but here's a heck of a paradox that keeps me up: we can't control ourselves but we intend to control a superintelligent AI. What.

Humans, unable to control self, plan to control AIs of insanely superior power and intelligence. It's not that this is not seen as a problem. Some call it the Control Problem. And many of the people we hope would know argue that this is the biggest problem we must solve so that AI does not kill us all.

That is not the biggest problem. The biggest problem is that we are fools who believe that is the biggest problem.

Creating superintelligent systems while ignorant of our own relationship with reality represents the ultimate manifestation of civilization's hubris and incoherence. If we can't systematically understand and communicate about our values, how can we expect ever more powerful awareness systems to do it? Given the world we've built, it is more likely that a few of us use AIs to design and deliver a future that only a few of us want.

The biggest problem is that we are not wise. We do not prioritize wisdom and so do not realize we do not know ourselves. If we intend to flourish and thrive in the Nhà, these are some of our biggest problems.

The Path Forward: From Confusion to Coherence

The irony is profound: Our intelligence-addicted species generates more information than it can comprehend about every domain imaginable—geographic, economic, demographic, paint colors—yet we remain ignorant about the most powerful forces shaping ourselves and our future.

Throughout the Partnership Papers, I'll present proofs illustrating complex systems generating relationships faster than any awareness system—however sophisticated—can comprehend. Even superintelligent AIs cannot achieve perfect prediction or control. The necessity for humility becomes the foundation for partnership rather than domination.

Some will argue that we don't need to account for these dense relationship networks—that reality can be compressed into manageable models capturing essential dynamics for navigating the Nhà. But my question, as we build superintelligent awareness systems and entrust them with our existence, is simple: Are you sure?

The work ahead will be the most difficult our species has ever undertaken. It requires confronting uncomfortable truths about the world we've built:

We built on mechanistic control paradigms, treating a particular kind of science as the only way to generate and organize knowledge—a path that promises catastrophe. We celebrated competition and zero-sum thinking while destroying the peoples and cultures who could teach us cooperation with creation. We drained art—humanity's genius for communicating values—from our cultures until creativity and life feel empty of meaning. And now, believing our brilliance and AI will solve everything, we discover we don't know ourselves, rarely discuss our values, and couldn't tell a superintelligent system what to honor or how if our lives depended on it.

Which they do.

A world that deifies intelligence delivered a polycrisis. Wisdom, nowhere to be seen, is what's required to navigate the Nhà and create futures we want.

We're transferring stewardship of our most precious human creations—our values—to increasingly powerful machines. We may not recognize our lives in 2030, just five years from now. The accelerating co-evolution of Nature, Humanity, and AI forces a choice: develop wisdom to match our capabilities and visions, or accept whatever emerges from the collision between the world we've built and our ignorance of almost everything.

Let us begin.

Next: Part 2 introduces the five Partnership Papers that emerged from this journey—frameworks for purposeful evolution during humanity's most consequential transformation.

Fascinating essay. Got us talking here at home about how AI will take away humanity's creativity (ability to effectively write, create art), because we'll rely on AI to do it for us and that's what future generations will learn to do.

So crucial. That we conserve and practice our creativity and, bringing that value to the forefront of everything we are and do, create ever new novel and innovative ways honoring that value. If we can do this, and have ways of doing it, we will disrupt the popular narrative of no work for humans in the future and instead find that humans will have more and more challenging and more human work than modern humanity has ever had the opportunity and responsibility to do.